#

Derivatives

This all gets a bit fuzzy for me. I never took multi-variable calculus and neural networks seem to rely on them for partial derivatives...I think. But the concepts outlined below should be a good summary. I still have to check these out to stress test my knowledge here.

#

Basics

The derivative of the function f(x) is the slope at point x, or how much the value changes at that point when increasing x by tiny amounts. In more explicit terms, it’s the value of:

f'(x) = \lim{h \to 0} \frac{f(x+h) - f(x)}{h}For the function 3x^2 - 4x + 5 we can see that the following is true

def f(x):

return 3*x**2 - 4*x + 5

x = 3

h = 0.001

f(x)

# 20.0

f(x + h)

# 20.014003000000002

h = 0.0000001

# 20.00000140000003So it’s increasing ever so slightly in the positive direction. To get the actual slope, we need to get the rise over run.

(f(x+h) - f(x)) / h

# 14.000000305713911Which if we take the derivative of f(x) where x = 3 we get f'(x) = 6x - 4 = 6*3 - 4 = 14 which matches our equations.

This is important, because as we start making complex chains of nodes (a neural net), we want to know the derivative of the output wrt the individual nodes. That way we can tell how we have to change that node to manipulate the output of the function.

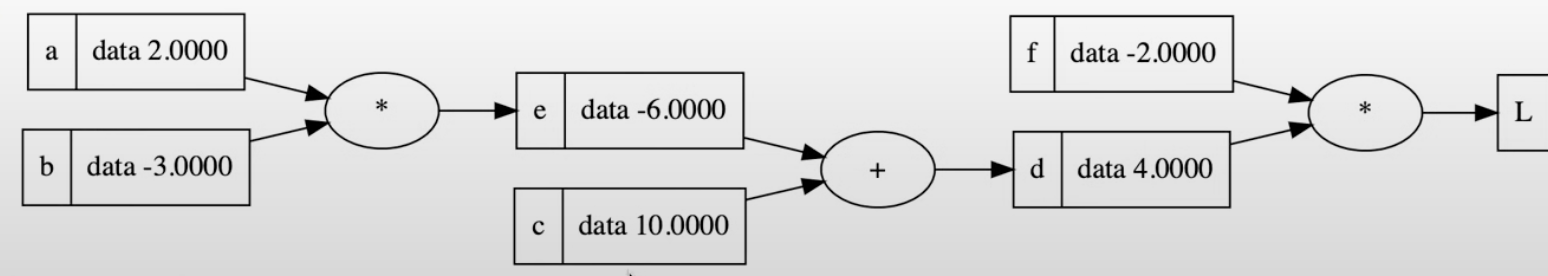

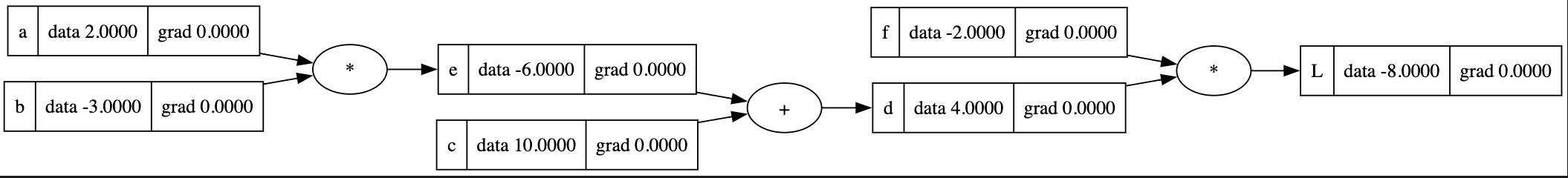

This is a good example, where we would want to know the derivative of L wrt c, so we know how to change c to impact L.

#

With respect to

I struggled a bit to understand/remember what derivatives of a variable w.r.t. a function/another variable means.

d = b \cdot a + c

\frac{dd}{da} = bYou would say this is “The derivative of d (where d is the function) w.r.t. a. And what that means is whenever I change a, how does that change the output of d? Using the Constant Multiple Rule we know that the derivative of a variable times a function is that variable times the derivative of the function.

\frac{d}{dx}(k*f(x)) = k * \frac{d}{dx}(f(x))Why do we know that? Because some mathematician made it up. So in the above, k=b and f(x) = a which gives us f'(x) = a' = 1 which leaves us with b. So each time we increase a by 1, d increases by b. What happened to c? Since it's not one of the variables being operated on, it gets treated as a constant and the derivative of a constant is 0. That's a property of taking a partial derivative.

Something important to think about is that in d if we changed c to c^2 the outcome is still the same. Because w.r.t a, c is constant. Meaning changing a has no impact on c. However if the equation was something like

d = a \cdot b + a \cdot c^2

We would then end up with a derivative of

\frac{dd}{da} = b + 2c

#

Chain Rule

The chain rule, in simple terms, says that if you have a composite function f(g(x)) and want to take the derivative of it, you can do f'(g(x)) * g'(x) . I.e. the derivative of the composite function is the inner function within the derivative of the outer function, multiplied by the derivative of the inner function.

#

As it relates to back propagation

More simply, as we navigate through back propagation, we will want to identify how one node affects the loss function. But this node could be one of many.

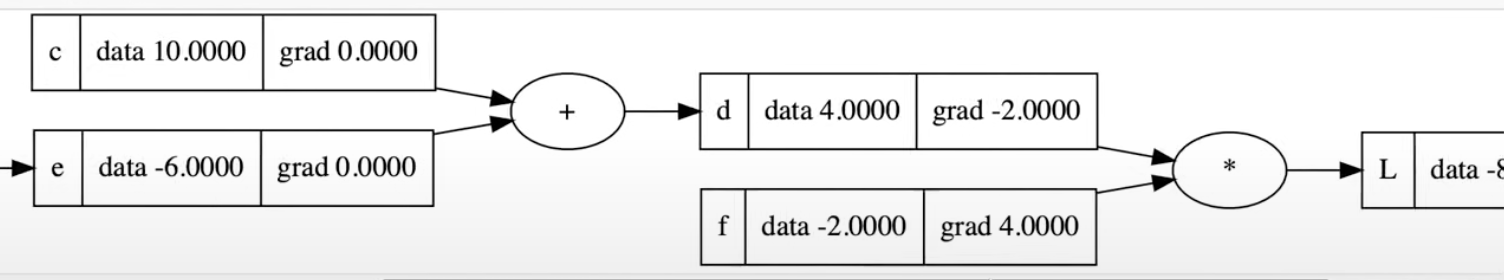

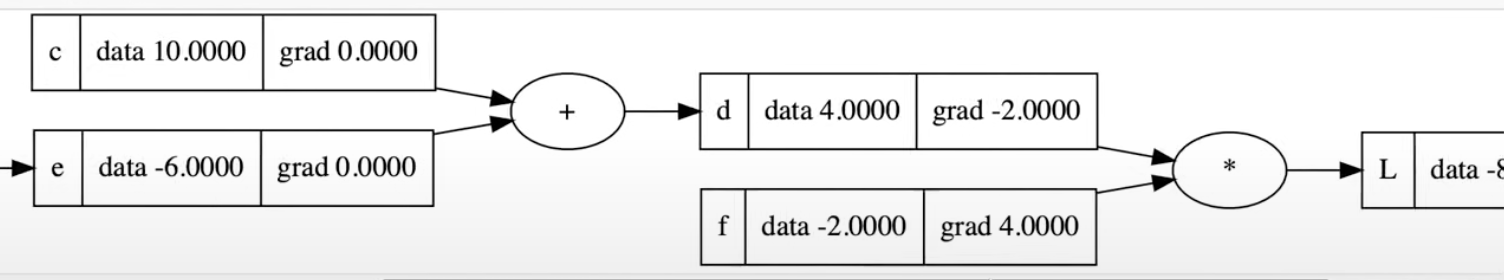

Using the above example, the local derivative of c \space w.r.t \space d is 1, because it’s

\frac{dL}{dc} = \frac{dL}{dd} \cdot \frac{dd}{dc}Which in this case is -2 \cdot 1 = -2. Why is \frac{dd}{dc}=1? See

Another cool thing here is that since the back propagation only relies on multiplying the local derivative with the grandparent derivative, the calculation can be arbitrarily complex. It doesn't have to be + or * between nodes, it can be anything as long as we can derive it. This is helpful when doing back propagation on a neuron that has an activation function, so we can derive the value inclusive of the activation function.

#

Addition

Doing the derivative of an additive operation w.r.t. a node is pretty easy. It equals 1. Why is that true? Take these nodes for example

d = c + e

\frac{dd}{dc} = \frac{d}{dd} c + \frac{d}{dd} e\frac{dd}{dc} = \frac{d}{dd} c + 0\frac{dd}{dc} = 1 + 0 = 1Why did e become 0? Remember that's a property of taking a partial derivative wherein any variables we are not currently working with become constants. And the derivative of a constant is 0.

Also don't forget that 1 is only the local derivative, we have to apply the

#

References

https://www.khanacademy.org/math/ap-calculus-ab/ab-differentiation-2-new/ab-3-1a/a/chain-rule-review